Chicago has accomplished some astounding feats as a city—reversing the river, raising the entire city a level, and rebuilding after a devastating fire, to name just a few. The boldness to innovate is not foreign to us. Recently, however, the tried and true Chicagoan method of “just do it” has succumbed to complicated approvals processes with multiple rounds of expensive consultants and increasingly long timelines.

More often than not, agencies like the Illinois and Chicago Departments of Transportation use limited computer models to simulate changes in street design or traffic flow. If they do not have the bandwidth to research these changes, the task is outsourced to out-of-state consultants charging exorbitant fees.

In 2021, Chicago hired a consulting company to assess and improve the streets of Humboldt Park and Belmont Cragin, zones that were designated “high crash community areas.” Though the final cost of the project pilot was only $38,000, the contract totaled $250,000, with nearly half of that amount spent on redundant research, superfluous recruitment, and a kickoff event, all of which spanned a four-month period that could’ve been otherwise utilized to get things done on the ground.1 In May 2024, the consultants hired finally completed what they called their Vision Zero report, but in the three-year interim, 7,351 car crashes occurred in the neighborhood, costing residents $8,500,000.2 We must ask ourselves in the face of this inefficiency: why are we spending so much time—and money—to make sure that wider sidewalks, protected bike lanes and narrower streets are safer when we’ve already known that for years? These millions in losses could have been prevented had we simply moved a bit faster.

I propose a new approach: don’t think; just do. Projects like the one in Humboldt Park and Belmont Cragin could be considerably more impactful, considerably sooner, if the time and money were spent more practically. As it stands, the results do not come close to matching the amount of effort exerted.

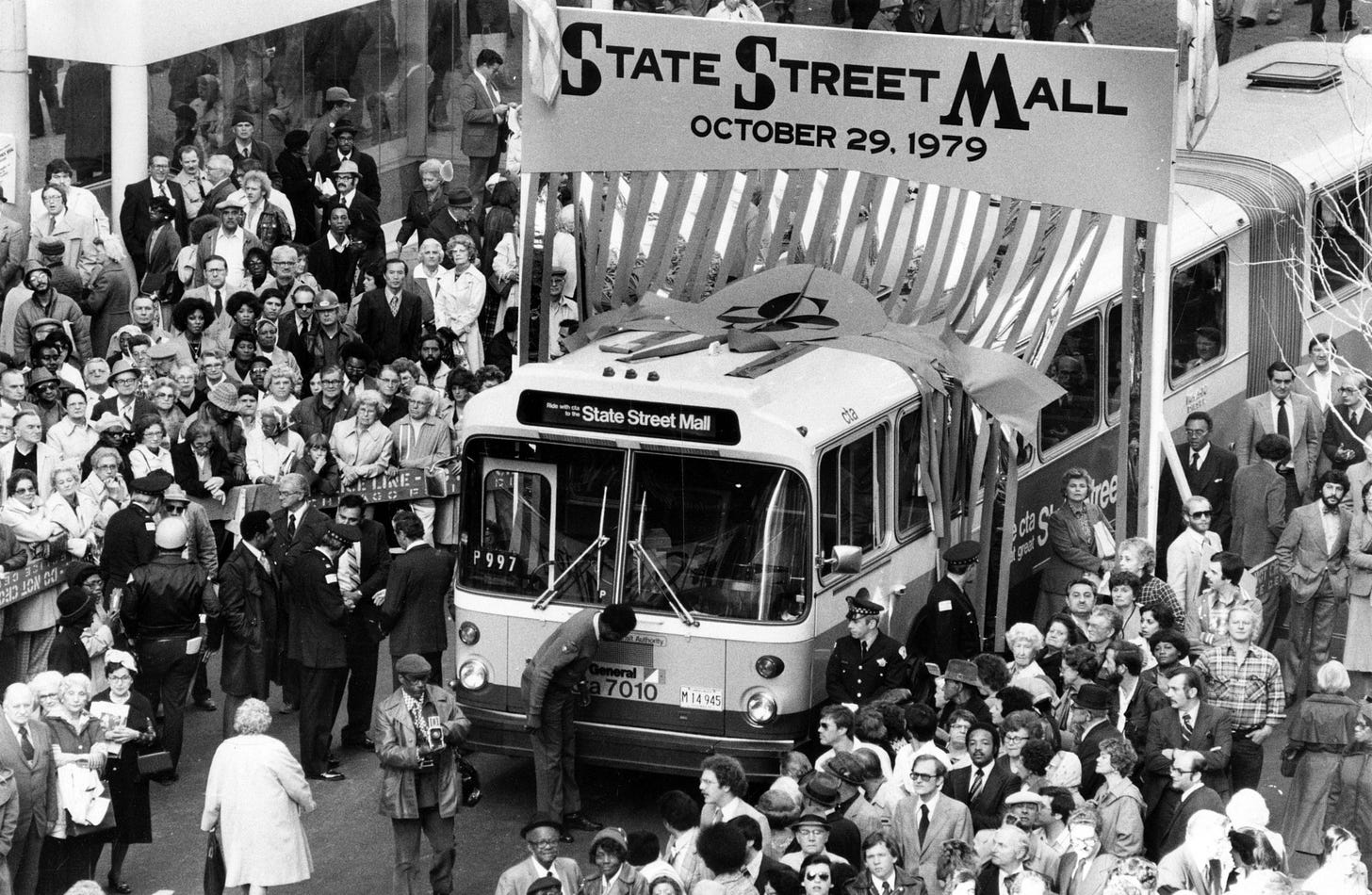

For an example of this mentality in action, let’s look elsewhere in the city and examine State Street. The corridor has seen plentiful attempts at pedestrianization throughout its history, such as a complete overhaul in the 70s that aimed to revitalize the area as a downtown mall for buses and pedestrians only. Sadly, fumes from buses and a lack of foot traffic somewhat foiled an otherwise well-intentioned plan.

More recently, however, State Street and The Loop as a larger neighborhood have seen record-breaking levels of housing construction and a return to pre-pandemic levels of pedestrian traffic, especially thanks to Sundays on State: a monthly summer event that draws in thousands to stroll, chat with neighbors and pop in and out of retail stores. This event gives the city the perfect opportunity to trial a pedestrian-only State Street in a new era that might be more receptive to the change. We can learn from our past mistakes and apply that knowledge to the now. Instead of conducting such a needlessly extravagant study and paying excessive consulting fees, we should simply test the proposed closure at a smaller scale, so we don’t end up making the same mistakes we made in 1979. Close the road for one afternoon and invite the community to test out the change. Observe and address pain points and neighbors’ concerns. Expand the test into a whole day—first once every six months, then once a month, then weekly. It isn’t rocket science.

Not only would this method more accurately demonstrate the plan’s real potential and showcase possible outcomes, but it would also increase civic participation. Public engagement should not be limited to surveys about computer renderings and open forums miles away from the project site. Instead, we should bring the vision directly to residents. Ask parents which pavement tile won’t wake up a sleeping baby in a stroller. Ask bikers which bike rack fits the most users. Ask the elderly which bench is the most comfortable for reading. Civil participation need not be quite so distant.

This desire for less red tape is hardly a novel idea in Chicago or in any political sphere, but in this modern era of excruciatingly bureaucratic approvals processes, we have forgotten how to effectively evolve into a forward-looking city. I’m reminded of a parable from David Bayles and Ted Orland’s novel Art & Fear in which they retell a story from the late Jerry Uelsmann. A photography instructor at the University of Florida, Uelsmann supposedly split his beginner class into two groups, one tasked with submitting just one photograph at the end of the semester to be graded on quality, and the other tasked with submitting as many as possible to be graded on quantity. At the end of the semester, the group who photographed a lot produced higher-quality photos because they were able to experiment, learn what worked and improve upon what didn’t. Those who were tasked with capturing one perfect photo instead spent more time theorizing how to achieve perfection than learning from their mistakes, which might have naturally led to a more perfect end product.

Endless cycles of surveys, consulting companies, and simulations are just like this endlessly distracting pursuit of theoretical perfection—they distance us from the real work and only increase the time citizens spend waiting for positive change. Mistakes in urban planning are unavoidable, and the beauty of a city sometimes lies in its flaws. But if we spend our entire lives thinking about how to avoid mistakes, at the end of the day, our city will do and have nothing.

Information about the 2021 contract were gathered from the City of Chicago Vendor, Contract, and Payment Search website

Statistics were gathered from the City of Chicago Vision Zero Dashboard